The Process of Emancipation

The Process of Emancipation

Emancipation as a legal reality was an unintended consequence of the U.S. Civil War. President Lincoln’s main goal was to keep the U.S. intact as a republic, focusing on returning the rebelling states to the Union. While Lincoln personally objected to slavery as a practice, he did not support abolition as a political agenda.

Enslaved Blacks understood the impact of the brewing contest on their status. The alarmist rhetoric of the slaveowners, and their invectives against the “Black Republicans,” characterized the Republicans and in turn the Union Army as sympathizers and potential liberators. They were also encouraged by the passage of an abolition measure for the District of Columbia in April 1861, despite its limited impact and provision for compensated emancipation.

Enslaved people acted on this logic early in the war, escaping to Union military lines as soon as they were in reach. In reaction to the number of runaways entering his camp at Fortress Monroe near Hampton, Virginia, and in consideration of the labor that enslaved Blacks were forced to provide to the Confederate Army, Union General Benjamin Butler announced in May 1861 that these laborers were “contraband of war,” and, as such, should not be returned to their owners. This action was later reinforced by the First Confiscation Act in August 1861, and the Second in July 1862. In this way, the agency of enslaved Black people in seeking freedom forced the U.S. government to belatedly create policies to accommodate and regulate self-emancipation.

As the war advanced, enslaved Black people in Florida sought safety in areas where the Union Army was present. The Anaconda strategy, devised to choke off the Confederacy economically by limited their ability to trade internationally, made Pensacola, Fernandina, Jacksonville, St. Augustine, and Key West areas of military contest.

After the bloody fighting at the Battle of Antietam in the fall of 1862, President Lincoln decided to move forward with a plan for widespread emancipation. On September 22, 1862, Lincoln announced in his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation his plans to enact emancipation, with some exceptions, in states that were rebelling against the Union. It was his hope in part, that as a military strategy, this would motivate the leaders of the Confederacy to come to the negotiating table to end the war. Failing to have the desired effect, the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863. In anticipation of the day, many African Americans held religious services on December 31, 1862, singing and praying until the moment that freedom arrive. This practice gave birth to the practice of Watch Night services in many religious institutions, a practice that continues in the coastal communities known as the Gullah Geechee Corridor between South Carolina and Florida.

The Emancipation Proclamation had its most immediate impact in Key West, as it was under Federal control. After some delay, formerly enslaved Blacks celebrated their emancipation on January 29, 1863, making it the earliest known emancipation celebration in Florida. Emancipation is also likely that enslaved Blacks observed and celebrated emancipation in Federally-controlled areas in East Florida like St. Augustine in January 1863.

For the majority of the approximately 62,000 enslaved Blacks in Florida, freedom would only become a reality after the victory of the U.S. Army over the Confederacy. That began to unfold on April 9, 1865, when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to U.S. General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia. With the defeat of the Confederacy, Union troops were able to not only spread the word of emancipation but to enforce it as well.

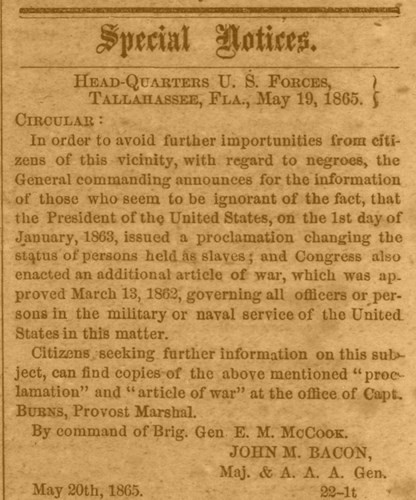

That news reached Tallahassee with the arrival of Brigadier General Edward M. McCook on May 10, 1865. He immediately began to spread the word of emancipation, printing notices in area newspapers of his intention to publicly read the Emancipation Proclamation on May 20, 1865. In a ceremony on that day, General McCook read the proclamation aloud, and flew the U.S. flag over the Florida State Capitol, signaling the defeat of the Confederacy in Florida, the supremacy of the U.S. government and its laws, and making emancipation a reality.

Nearly a month later, on June 19, 1865, Union General Gordon Granger repeated the actions of Gen. McCook, this time in Galveston, Texas, announcing emancipation in that state. To be sure, the announcement of President Lincoln’s proclamation did not always translate to immediate liberation. Union soldiers could not be everywhere, and there was widespread resistance by former slaveowners. Still, the reality of emancipation would continue to settle, finally becoming federal law with the passage and ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on December 6, 1865, ending the practice of slavery in the United States, except for the purposes of punishment.