Emancipation at Key West

Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

Key West’s slavery and emancipation story is quite different from those of other parts of Florida. From first settlement in 1822, slavery was a part of Florida Keys culture, and by 1860, of 2,913 people at Key West, 451 of them were enslaved. But, as the islands were too small to support large-scale agriculture, the Florida Keys never developed a plantation economy. Instead, the enslaved were often forced to work as domestic servants and mariners. But surprisingly, the largest single employer of slave labor in the Keys was the US government, which utilized bondsmen in the construction of Fort Taylor on Key West and Fort Jefferson at the Dry Tortugas. For many years, Key West slave owners rented their people to the Army Corps of Engineers to help build the large masonry structures.

Even though construction of the forts was not completed by the outbreak of the Civil War, their presence kept the Florida Keys under Union control. In January of 1861, shortly after Florida seceded, Army Captain James Brannan of the 1st US Artillery at Key West, quietly marched his troops into Fort Taylor in the dead of night, while the town slept. With Army troops then manning the fort and its cannons, and Navy ships guarding the harbor, the US military had control of the city. Shortly after, US forces took command of Fort Jefferson. The confederates had been outwitted and never gained a foothold in the Florida Keys. Slavery, though, continued as it always had.

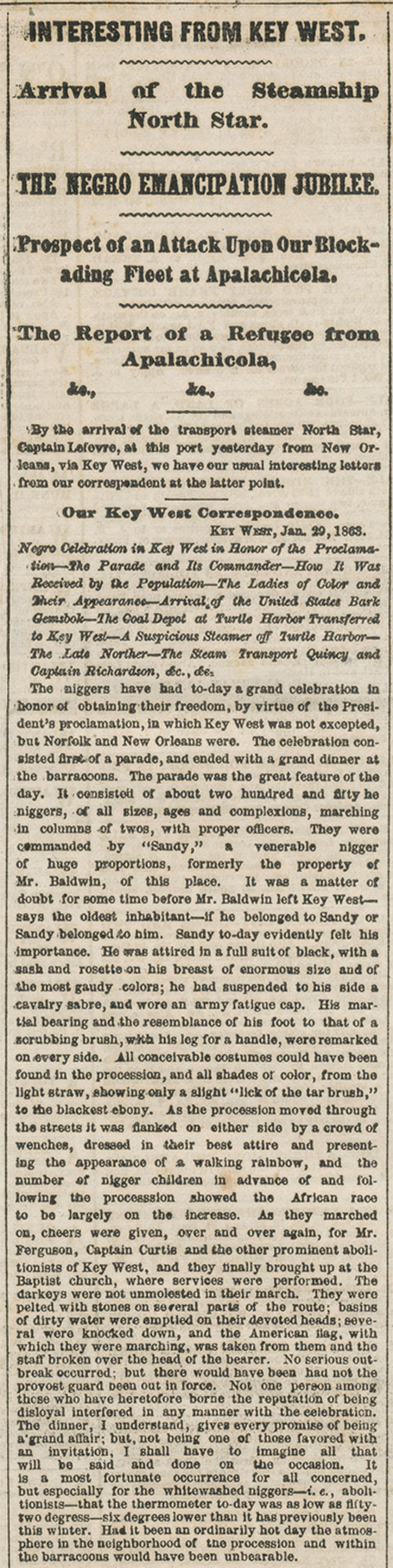

Because Key West was under US control, when President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, the edict was valid and enforceable on the island. It took some time for word to travel from Washington to the remote community, but on January 18, the news arrived. An eyewitness wrote, “The proclamation arrived by yesterday’s mail…the colored people of all ages wear cheerful countenances, with a manner and demeanor that plainly indicates both gratitude and appreciation.” But not everyone was pleased. Some felt the proclamation was unfair because it released property from Key Westers who had remained loyal to the Union, depriving them of their deserved wealth. For others, the upheaval of a long-standing social order was distressing. When news of the proclamation arrived, one resentful islander wrote, “The colored ‘gemmen’ of Key West and elsewhere must not suppose that because they are free, we, the whites, are slaves, for if they try that on, as I think they will, woe betide them.”

On January 29, after having had some time to prepare a proper celebration, Key West’s Black community commemorated emancipation with a parade and a dinner. Two hundred and fifty men marched through the island’s streets in two columns, flanked on either side by women and children, everyone dressed in their best for the occasion. The procession was headed by Sandy Cornish, the island’s most successful farmer and the de facto leader of the Black community. Cornish, dressed in a black suit with sash and saber, limped as he strode because, years earlier, he had maimed himself in a bid to make himself useless as a slave. The marchers were occasionally pelted with rocks and doused with water by confederate sympathizers, but they stopped to cheer at friendly residences. The parade ended at the Baptist Church, where a religious service was held. After that, at three o’clock in the afternoon, everyone made their way to the “baracoons,” a compound on the southwestern point of the island that had been built in 1860 to accommodate 1400 African refugees rescued from slave ships. There, the newly freed Key Westers were joined by US military officers and supportive members of the community. Celebratory speeches and toasts were given, food was served, and the party carried into the night.

Besides setting the enslaved free, the emancipation proclamation had another direct outcome at Key West: A secondary clause of the document mandated that “such [emancipated] persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.” On February 3, 1863, just days after the celebrations on the island had ended, Col. James Montgomery arrived in Key West to begin recruiting men for the new 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Regiment of the US Colored Troops. The enlistment drive was successful, and Montgomery soon had 126 new recruits. The men of the 2nd South Carolina left Key West and headed to Hilton Head to begin their service. From there, the new regiment, aided by the renowned abolitionist Harriet Tubman, would soon see action in a raid on Combahee Ferry. In the attack, which destroyed cotton crops and several South Carolina plantations, nearly 750 enslaved people were liberated from Confederate control. The effects of emancipation at Key West had quickly magnified: The arrival of the proclamation changed the lives of enslaved islanders immediately and forever, which allowed them to, within weeks, liberate hundreds of other people and help shape the outcome of the Civil War.